When we read about impressive new drugs, do we really understand what the percentages quoted mean?

You may need to make medicines-related choices—particularly for cancer, but other illnesses too. To make rational decisions you MUST understand the numbers your doctor quotes. He won’t deliberately mislead, but it is easy to misunderstand statistical data.

So let me give you an inkling—not a maths lesson, just a few tips to help you ask the right questions.

Last week the BBC headlined: ‘Breast cancer: Taking hormone drugs for up to 15 years can reduce risk … cancer recurrence was cut by 34%’

Wow. Impressive. But let’s look closer: In that particular study, 95% of those who took the treatment for 15 years were cancer-free, compared to 91% who stopped at 10 years.

Hang on – 95% isn’t that different from 91%. How is that cutting risk by 34%?

Well (and this is important) improvement percentages quoted in newspapers, and by doctors and scientists, are often described in relation to the original risk.

In these patients, the original risk of cancer recurring was only 9%, so any improvement would appear large relative to 9%. If the original risk had been higher, the same benefit would have appeared less.

OK that’s the bottom line. But for the curious, another example:

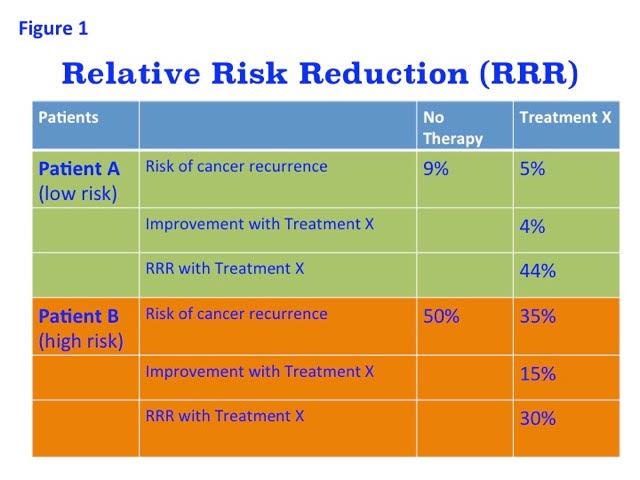

Relative Risk Reduction (RRR) is a statistic often used to describe drug benefit. It is what it says—the reduction in risk (eg risk of death, or disease recurrence) relative to the original risk, ie the actual risk improvement divided by the original risk.

The Table shows an example. Patient A has a low risk of cancer returning (9%); Patient B’s cancer is more likely to recur (50%).

You can see from the Table that Patient A’s risk will only decrease by 4% with Treatment X, whereas Patient B’s will decrease by 15%.

Knowing this, Patient B should be more inclined to take treatment X than Patient A.

However, if Patient A’s doctor describes the benefit as RRR (see Table), then Patient A’s risk appears to decrease by a massive 44%. Consequently Patient A may have wildly inaccurate expectations for the treatment. The doctor isn’t tricking him, RRR is scientifically valid, but you need to know what it means.

This example highlights another point. Sometimes we only know that a treatment works in most people. However sometimes there is more information about how much it works in different patients eg Patient B would respond to Treatment X more than Patient A.

If available, you need specific information on the benefit for YOU. This could influence your decision, particularly for a treatment which has significant side-effects.

So, in summary:

If your doctor uses percentages to explain a treatment benefit, ask:

1. Exactly what do the numbers mean?

2. By how many percentage points should you improve on treatment?

3. Is there more specific information for your particular situation?

Don’t be frightened to ask your doctor for more information—he wants you to understand and may not realise when you don’t.

By Dr K Thompson, author of From Both Ends of the Stethoscope: Getting through breast cancer – by a doctor who knows

http://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B01A7DM42Q http://www.amazon.com/dp/B01A7DM42Q

http://faitobooks.co,uk

Note: These articles express personal views. No warranty is made as to the accuracy or completeness of information given and you should always consult a doctor if you need medical advice

Further information:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-36455719

http://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMoa1604700

http://www.breastcancer.org/risk/understand/abs_v_rel

http://www.nps.org.au/glossary/absolute-risk-reduction-arr