First let me say that I am one lucky, lucky writer. Long have I dreamt of eating at Dubrovnik’s only Michelin starred restaurant, and on my last visit, I did it. It’s a very special place (with prices to match) but I had cause for celebration – it was publication day for The Collaborator’s Daughter, my novel set in the city.

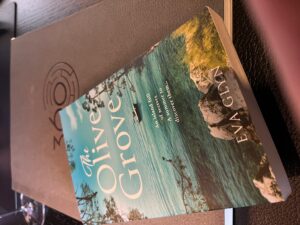

I had visited Restaurant 360 before, but only through the pages of The Olive Grove. Where else would wealthy businessman Josip Beros take Damir to impress him?

I had visited Restaurant 360 before, but only through the pages of The Olive Grove. Where else would wealthy businessman Josip Beros take Damir to impress him?

‘The design of the place alone took Damir’s breath away, the cubed rattan furniture in turquoise and grey in the lower courtyard contrasting in both colour and style with the honeyed stone of the old fort into which it was built.’

It is, indeed a stunning location, and in the summer open air tables grace the tops of the walls giving stunning views of the harbour, but on a breezy evening right at the beginning of April I was pleased we would be eating inside.

Everything about Restaurant 360 is precise, except for the service which is as friendly as it is knowledgeable about the food and wine they serve. As well as a la carte choices, there are two tasting menus; Antalogica, which showcases the chef’s latest signature dishes, and Republika, a modern take on heritage dishes from the time of Dubrovnik’s Ragusa republic.

We were delighted when the sommelier was able to match a different Croatian wine with each course. Croatian wines are hugely underrated (and my husband knows a thing or two about wine, having worked in the industry) and we were able to enjoy a selection of the best with our meal. We were especially impressed with a Grk from Lumbarda on Korcula. All the more delicious to me because that’s where The Olive Grove is set.

We were delighted when the sommelier was able to match a different Croatian wine with each course. Croatian wines are hugely underrated (and my husband knows a thing or two about wine, having worked in the industry) and we were able to enjoy a selection of the best with our meal. We were especially impressed with a Grk from Lumbarda on Korcula. All the more delicious to me because that’s where The Olive Grove is set.

All the food was wonderful, but it was with fish that Restaurant 360 excelled. We do sometimes treat ourselves to Michelin starred food, and some of the dishes bettered anything we have eaten. Anywhere. The absolute star of the show was what sounded an unlikely combination of smoked eel, foie gras, melon, and date cream. The man who thought that one up, and then delivered it, is some sort of genius.

A great deal of time goes into perfecting the dishes. Our waiter told us that the ‘fish soup’ accompanying the brodet (a very traditional Croatian dish) of grouper and clams had gone through almost forty iterations before it was deemed worthy of serving. And I would imagine it was the same with everything else; the sea bass with leek and langoustine was one of the most amazing things I have ever tasted. And the scallop tartar with kohlrabi and yuzu gel was as delightful as it was refreshing.

Great care was taken with my gluten free diet and I felt very safe all evening. The bread was delicious and plentiful, accompanied by a colourful array of butters, and where a dish could not be adapted, (as with one of the amuse bouche) the chef made something specially for me. Nothing was too much trouble for kitchen or staff, which made dining at 360 a wonderful experience.

Great care was taken with my gluten free diet and I felt very safe all evening. The bread was delicious and plentiful, accompanied by a colourful array of butters, and where a dish could not be adapted, (as with one of the amuse bouche) the chef made something specially for me. Nothing was too much trouble for kitchen or staff, which made dining at 360 a wonderful experience.

I couldn’t resist taking a copy of The Olive Grove with me, and gave it to our fabulous sommelier when we left. He was delighted to hear it was set on Korcula, where he and his wife had honeymooned. It seemed such a small thank you for a night we will never forget.