I would never have even realised Dubrovnik had a Jewish Museum if I hadn’t been researching the city’s Jewish community during the Second World War. As it happens, their story – and the museum itself – became an important part of The Collaborator’s Daughter.

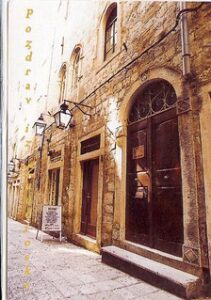

I tracked the museum down online first. There are walking tours of the city with a Jewish focus that appear to be aimed specifically at the cruise passengers, and through this I discovered the heart of the Jewish community in the old town. The name of its location, Zudioska (Jewish) Street might have given it away if I’d thought about it.

I tracked the museum down online first. There are walking tours of the city with a Jewish focus that appear to be aimed specifically at the cruise passengers, and through this I discovered the heart of the Jewish community in the old town. The name of its location, Zudioska (Jewish) Street might have given it away if I’d thought about it.

As with many medieval trading cities the Jewish community in Dubrovnik were important and the synagogue is one of the oldest Sephardic ones in Europe. It is on the top floor of the rather anonymous building and is a beautiful and calming sacred space even today. The dark wooden seats are rich with age and the Wedgwood blue decorations on the ceiling reminiscent of the Mediterranean sky.

Even more interesting to me was the museum that takes up the floor below. It is tiny but showcases the community’s history so well, from the fabulously embroidered vestments and ornate fourteenth century torah scroll that represent the Jews’ proud history, to a second room with chilling artefacts from World War Two.

Even more interesting to me was the museum that takes up the floor below. It is tiny but showcases the community’s history so well, from the fabulously embroidered vestments and ornate fourteenth century torah scroll that represent the Jews’ proud history, to a second room with chilling artefacts from World War Two.

Compared to other parts of Europe, overall Dubrovnik’s Jews suffered less because initially at least they were under Italian control. While Croatia’s (and yes, it is correct to use that term for the period) home grown fascists persecuted the faith with even more vigour than the Germans, in this small enclave they were safe. For a while at least, and their numbers grew.

Then, in 1942 the Italians were told the clamp down. Curfews were imposed, yellow armbands issued. All the awful paraphernalia of ethnic hatred. Finally in the November the eighty or so members of the community were interned near the harbour at Gruz and on the island of Lopud. Eventually they were moved north to a larger camp at Rab, and during the chaos resulting from the Italian surrender the partisans took the area and a majority were saved. In all twenty-seven of the Dubrovnik Jews died, many more moved to Israel, and the community never recovered.

Then, in 1942 the Italians were told the clamp down. Curfews were imposed, yellow armbands issued. All the awful paraphernalia of ethnic hatred. Finally in the November the eighty or so members of the community were interned near the harbour at Gruz and on the island of Lopud. Eventually they were moved north to a larger camp at Rab, and during the chaos resulting from the Italian surrender the partisans took the area and a majority were saved. In all twenty-seven of the Dubrovnik Jews died, many more moved to Israel, and the community never recovered.

Although the synagogue is rarely used, helpful volunteers are available to show visitors around and to talk about the artefacts and history. The museum is open all day, every day, and is well worth half an hour of anyone’s time.