Every day we read on the Internet, in newspapers or in magazines about wonder drugs. With all these miracle cures around it is surprising that so many of us still suffer illness. Surely we just need to pop one of these pills and all will be well?

But maybe, just maybe, some of these potions can’t cure cancer, can’t make people with arthritis dance in the streets and can’t make you lose ten inches off your waist-line in a week?

If you have incurable cancer, or constant arthritic pain, you wouldn’t want to miss a useful treatment. So how can you know whether claims are genuine or snake oil?

Approved medicines are tested in numerous clinical studies, usually in thousands of people. Study data are scrutinised by regulatory authorities (FDA in USA and EMA in Europe) before doctors can prescribe them. Thus there is firm evidence that they work, and a great deal is known about side-effects or safety issues.

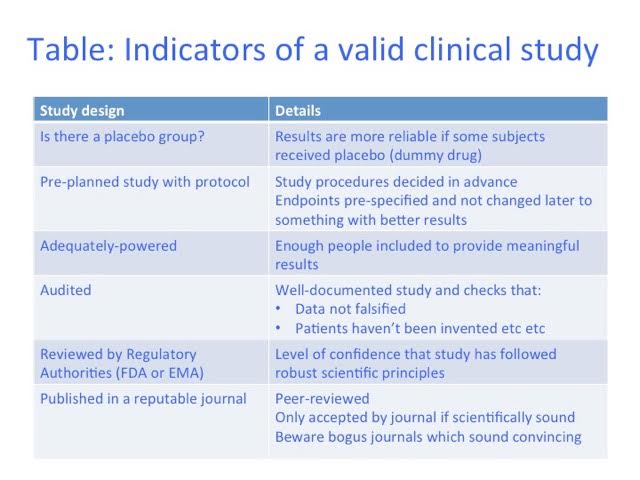

However, anything can be advertised on the Internet – Google has no truth filter. Impressive-sounding study results may not be scientifically sound. So here are some clues to help you assess them (See Table):

1. Has the ‘medicine’ been tested against placebo (dummy medicine)? If people believe they are receiving a beneficial treatment, they often feel better, regardless. Most studies should include some patients who only receive placebo, to make sure any benefit is due to the real medicine.

2. Measures of benefit (endpoints) should be chosen before a study starts. Eg an influenza medicine may measure fever. If fevers don’t improve, one can’t then change the endpoint to, say, sore throat, just because these improved more. Some symptoms will improve by coincidence, and it isn’t valid to cherry-pick the best results. This is often done in unregulated ‘studies’ and can make a treatment look better than it is.

3. Always check how many people were tested. If a study only had two patients, and one received real medicine and one placebo, even if the patient on the real medicine did better, it could have been due to chance. Statisticians calculate how many patients are needed to give a reliable result. Unregulated studies rarely include enough people.

Unapproved studies are not always checked, so there is more opportunity to ‘cheat’—results may be changed, ‘patients’ invented, or data from any patients who didn’t improve may be removed. Where the study was performed, and by who, may give reassurance on this, or not.

A respectable study will be written up as a report, and will be published in a good scientific journal. Be careful though – some ‘journals’ have impressive titles but are not what they seem. You can check them on Cite Factor (see below) to be sure.

I hope this helps you decide what you can believe. If in doubt, do ask your doctor’s opinion. And remember, if something seems to good to be true – then it may well be exactly that.

By Dr K Thompson, author of From Both Ends of the Stethoscope: Getting through breast cancer – by a doctor who knows

http://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B01A7DM42Q http://www.amazon.com/dp/B01A7DM42Q

http://faitobooks.co,uk

Further information:

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/info/understand

Note: These articles express personal views. No warranty is made as to the accuracy or completeness of information given and you should always consult a doctor if you need medical advice