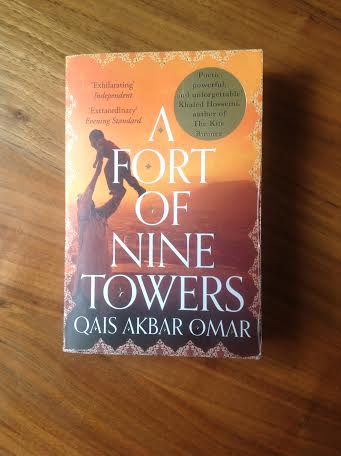

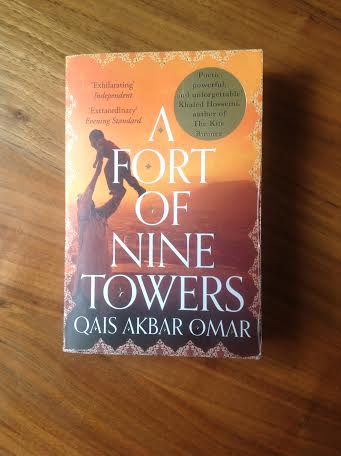

I have to be honest. I have put off writing this review. Which may seem weird considering the fact that A Fort of Nine Towers is one of the most important books I have ever read. Many books change you, give you enjoyment, make you think, even change your outlook: A Fort of Nine Towers does most of these, but it also touches your soul, your heart and then breaks them a little. As a Western woman, with all of the privilege that entails, reading this book is an eye-opener and a game changer.

I read papers, I watch the news, I watch documentaries and read books. I stay involved in politics and world events, but this tale of a young boy growing up in Afghanistan should be required reading for every one in the Western world (and beyond).

How much the human spirit can endure is both interesting and fascinating. The same with the human body. Qasis Akbar was only eleven when a brutal civil war broke out in Kabul. For Qais, it brought an abrupt end to a childhood filled with kites and cousins in his grandfather’s garden: one of the most convulsive decades in Afghan history had begun. Ahead lay the rise of the Taliban, and, in 2001, the arrival of international forces.

Called ‘poetic, powerful and unforgettable’ by The Kite Runner author Khaled Hosseini, A Fort of Nine Towers is the story of Qais, his family and their determination to survive these upheavals as they were buffeted from one part of Afghanistan to the next. Drawing strength from each other, and their culture and faith, they sought refuge for a time in the Buddha caves of Bamyan, and later with a caravan of Kuchi nomads. When they eventually returned to Kabul, it became clear that their trials were just beginning.

A lot of this book is horrifying, the inhumanity from one human to another, but there is also hope. Qais apologises to the reader for the stories he tells, knowing they will never leave your mind: stories of pits full of skulls, women being gang-raped, a man called ‘Dog’ who tortures and kills people by biting them. Something that happens to Qais and his father, but only after they have seen a row of dead naked people, some tourists, all in a row, horror as their death masks.

This book is also important as a way to dispel propaganda. Rather fascinatingly Qais writes about hearing talk of a rich Arab named Bin Laden (Yes, that one), who lived near Qais in a big house which used to be owned by someone called the Pimp of The King. The place was always covered by Taliban and they would drive black Land Cruisers and have big meetings there. So Osama Bin Laden was in Afghanistan. I am not saying this has made me pro-war, I believe lies were told, but this piece of information, and the stories of the Taliban; what they did, their brutality, what happened to women…Westerners don’t just have a duty to other Westerners and certainly not just to other white people. We can not just turn a blind eye. When I read the book and got to the end, I see how the invasion of Iraq also benefited Afghanistan. I am more educated but I want to learn even more, talk to more Afghans. The book even prints out the rules for women and information the Taliban distributed after it took over Kabul. These include toppling walls on homosexuals (if they live it means they weren’t homosexuals) and women should not step outside of their residence…she belongs to only one man (Husband) or soon she will be property of a man (Husband). And the ironically illiterate: women do not have as much brains as men, therefore they cannot think wisely as man. These ended with ‘Sincerely! The Taliban rules’. Like some illiterate teenager would graffiti on a wall.

I learned a lot reading this book. Some I already knew but it was reinforced: the Taliban are evil. Horrible peasants who use religion as an excuse to murder and torture and rule, the horror of organised religion and the damage it can cause, how privileged anyone is to be born in Britain or the US, how they have no excuse whatsoever not to make something of their lives, when there are people like Qais, who survived a brutal war, who saw the people he loved killed, who saw such horrifying things at such a young age. But more importantly I was more educated after reading this book, more compassionate. I was sadder, emotional but with a fire in my belly: knowing that every human being must do their best, and what happened in Afghanistan should never be forgotten. God knows what will happen when US troops pull out soon. I only hope the Taliban do not return, but I fear that they will. It is too awful a thought to even contemplate and God help Afghanistan if they do.

You can buy A Fort of Nine Towers here. I highly recommend that you do.

What do you think?

The UK must not abandon Afghan women, actress Olivia Colman warned after featuring in documentary which explores the dangers women face while undertaking ordinary jobs there.

The UK must not abandon Afghan women, actress Olivia Colman warned after featuring in documentary which explores the dangers women face while undertaking ordinary jobs there.